Abstract

- Relapsing polychondritis is a rare multisystemic autoimmune disorder of unknown etiology and characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation affecting the cartilaginous tissues. Otologic manifestation such as auricular chondritis is one of the most frequent presenting symptoms in relapsing polychondritis, and inner ear symptoms, such as hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo, may develop in 7% to 42% of the patients. In this study, we present a 42-year-old male patient with relapsing polychondritis, who experienced two separate episodes of acute vestibular syndrome at the interval of 6 years. At the first vertigo attack, the patient showed left-beating spontaneous nystagmus with sudden hearing loss on the right side, and a bithermal caloric test revealed canal paresis on the right side. At the second vertigo attack, he showed right-beating spontaneous nystagmus, and a bithermal caloric test, compared to that during the first vertigo attack, revealed additional decrease in caloric response on the left side.

-

Keywords: Relapsing polychondritis; Magnetic resonance imaging; Vertigo; Intracanalicular mass

-

중심단어: 재발성 다발연골염, 자기공명영상, 현훈, 내이도내 종물

INTRODUCTION

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) was first described in 1923 by Jaksch-Wartenhorst under the term of “polychondropathia” and was considered as a degenerative disease [1]. RP is a rare multisystemic autoimmune disorder of unknown etiology. RP is characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation affecting the cartilaginous tissues, leading to fluctuating but progressive course of anatomical deformation and functional impairment of involved structures. All types of cartilage can be affected such as the elastic cartilage of the ears and nose, hyaline cartilage of peripheral joints, fibrocartilage of the axial skeleton, and cartilage of the tracheobronchial tree. RP may also affect other proteoglycan-rich structures such as eye, heart, blood vessels, and inner ear. Auditory or vestibular dysfunction due to inner ear involvement has been reported in 7% to 42% of patients with RP [2-4]. McAdam et al. [2] proposed diagnostic criteria for RP, which requires three or more of the following clinical features, even without biopsy confirmation: bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation, respiratory tract chondritis, and vestibulocochlear dysfunction. Damiani and Levine [5] proposed that definitive diagnosis of RP can be made when one or more of the clinical features are present with biopsy confirmation.

In the present study, we report a case of a 42-year-old male patient with RP, who experienced two episodes of acute vestibular syndrome at the interval of 6 years. Internal auditory canal (IAC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated mild focal enhancement in the right vestibule, cochlea, and vestibular nerve during the first vertigo attack, and revealed a small enhancing nodule in the right IAC fundus.

CASE REPORT

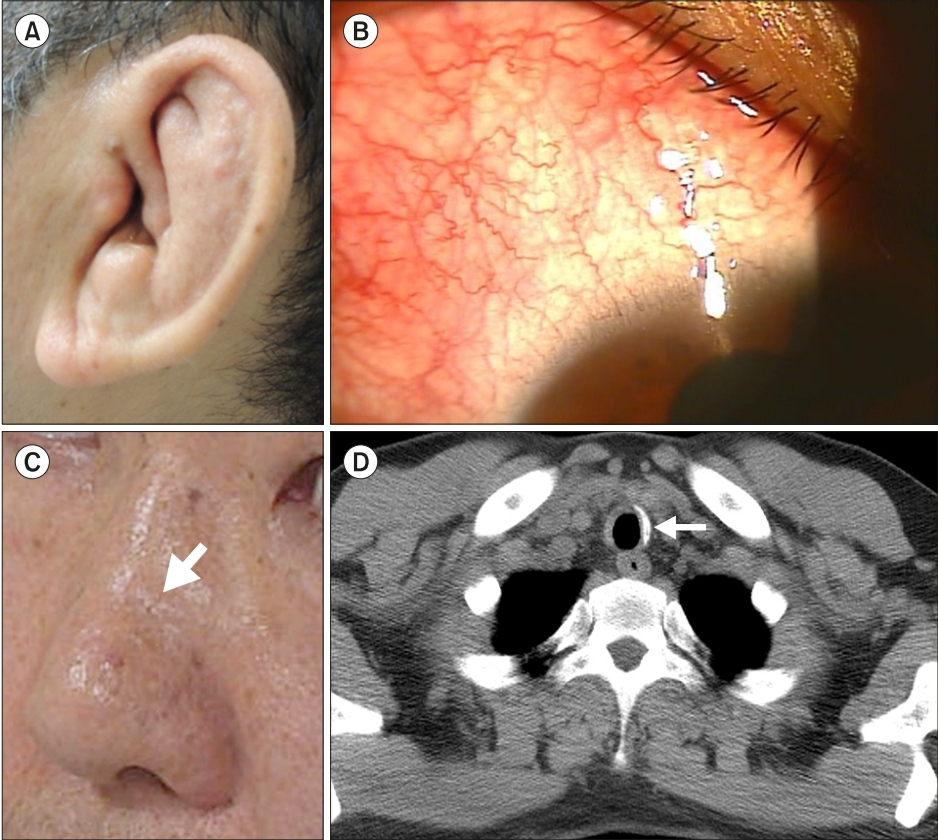

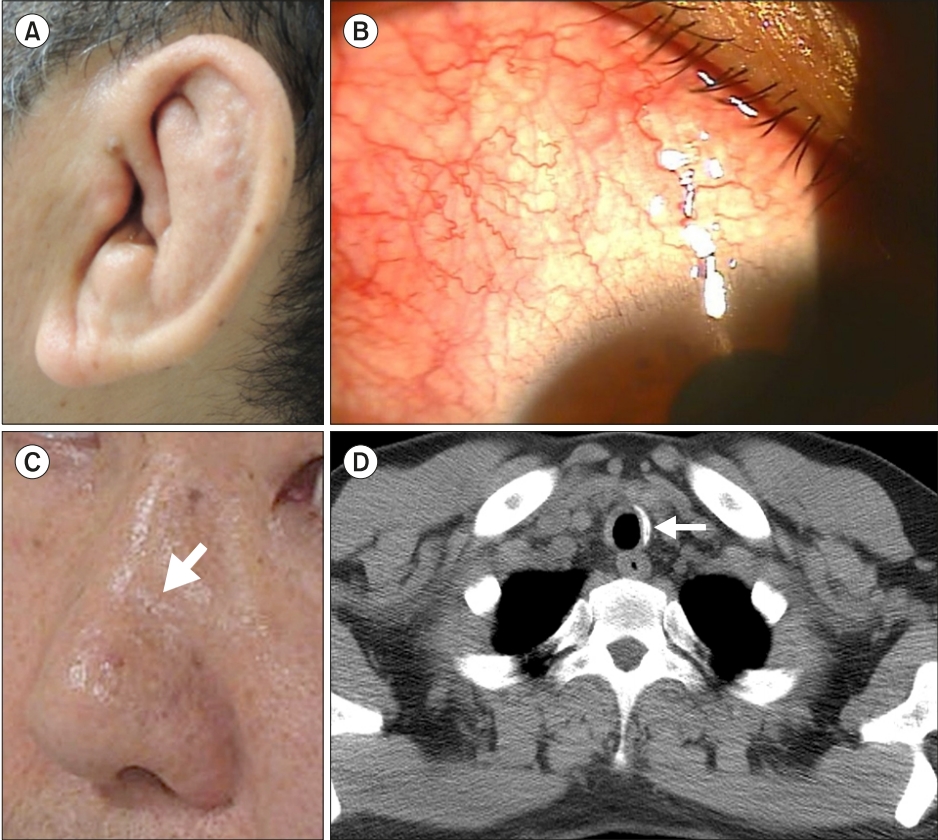

A 41-year-old male patient, who had been previously diagnosed with RP 8 years ago at another hospital, was admitted to our hospital with symptoms of acute vestibular syndrome which started since 72 hours ago. This was the second vertigo attack, and he had experienced the first vertigo attack 6 years ago. The patient showed five features of McAdam’s diagnostic criteria for RP including vestibulocochlear dysfunction, bilateral cauliflower pinna deformity (Fig. 1A), episcleritis (Fig. 1B), saddle nose deformity (Fig. 1C), and thickening of tracheal cartilage (Fig. 1D).

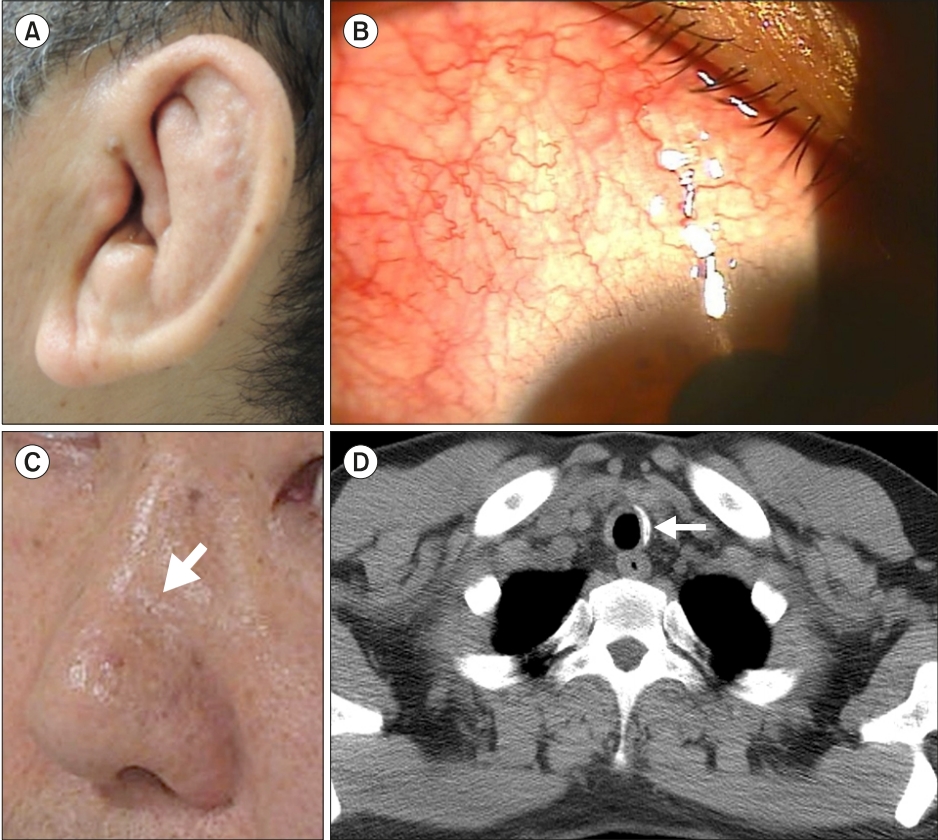

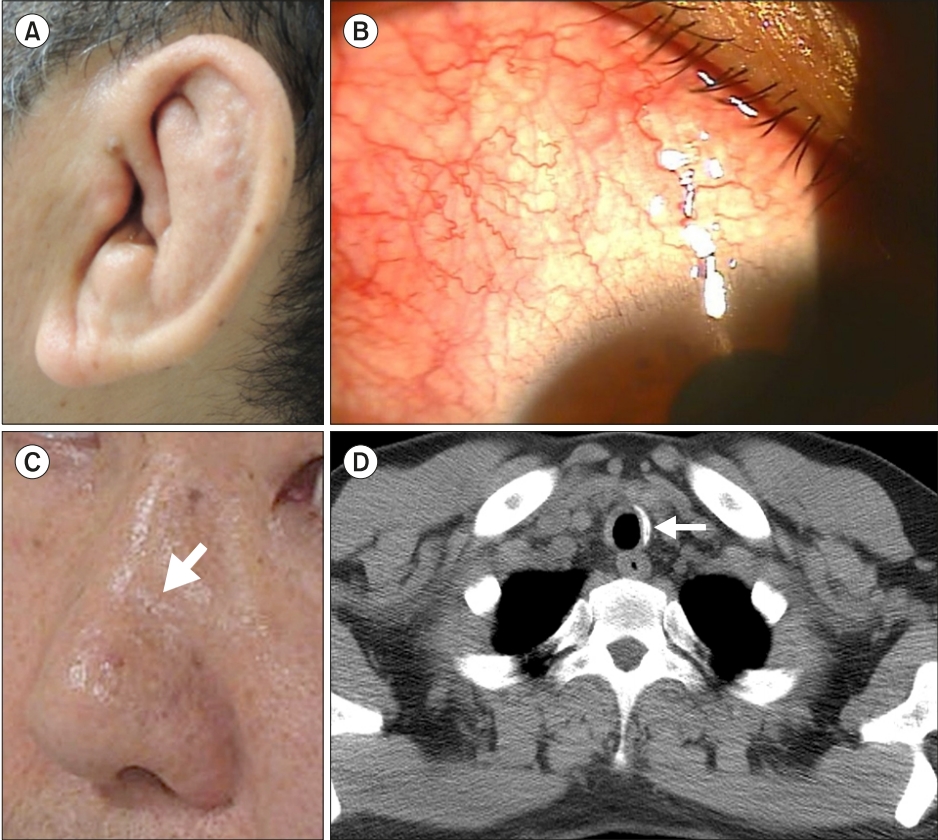

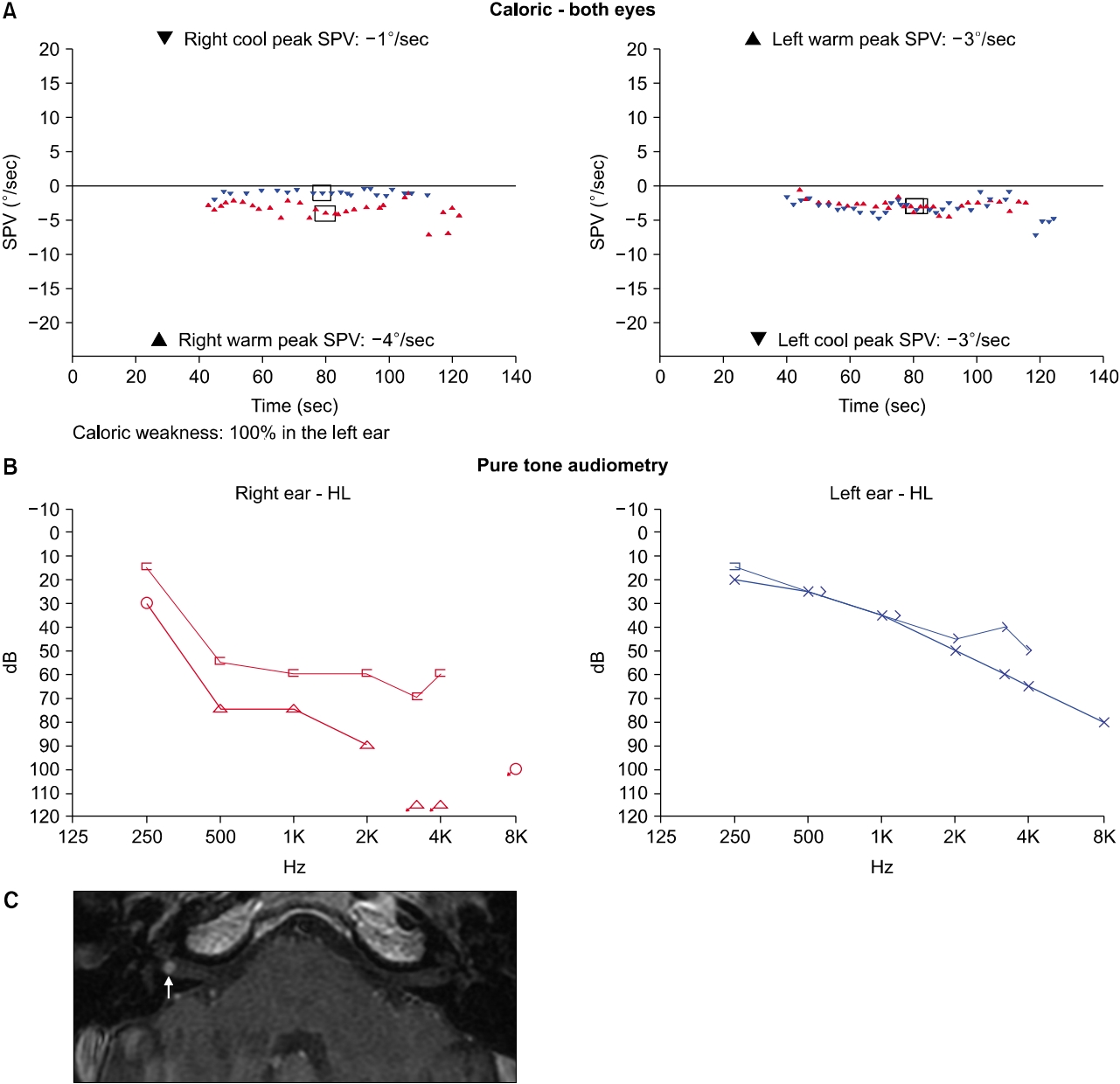

At the first vertigo attack 6 years ago, acute vestibular syndrome was accompanied by auditory symptoms on the right side including sudden hearing loss and tinnitus. The patient showed left-beating spontaneous nystagmus (Supplementary Video 1), and bedside head impulse test revealed catch-up saccades on the right side. Neurological examination revealed no other focal neurologic deficit. A bithermal caloric test showed a canal paresis on the right side (Fig. 2A), and hearing threshold was worse on the right side in pure tone audiometry (PTA) showing severe mixed hearing loss with air conduction (AC) threshold of 81 dB (mean threshold at 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 kHz) and bone conduction (BC) threshold of 54 dB (mean threshold at 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 kHz) (Fig. 2B). Because the patient did not show any evidence of the external auditory canal stenosis or otitis media with effusion, the associated conductive hearing loss may, although the cause of air-bone gap is not clear, be attributed to the accompanying middle ear lesion such as stapes fixation [6]. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted IAC MRI demonstrated that mild focal enhancement of the right membranous labyrinth including the vestibule, cochlea, and vestibular nerve, suggesting a combination of neuritis with labyrinthitis (Fig. 2C). Although the patient had been taking oral prednisolone from the rheumatology department, he was administered systemic high dose steroids (prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day for 4 days, and then tapered off during the subsequent 10 days). The right hearing recovered to the level with AC threshold of 56 dB and BC threshold of 41 dB, and vertigo gradually resolved after treatment.

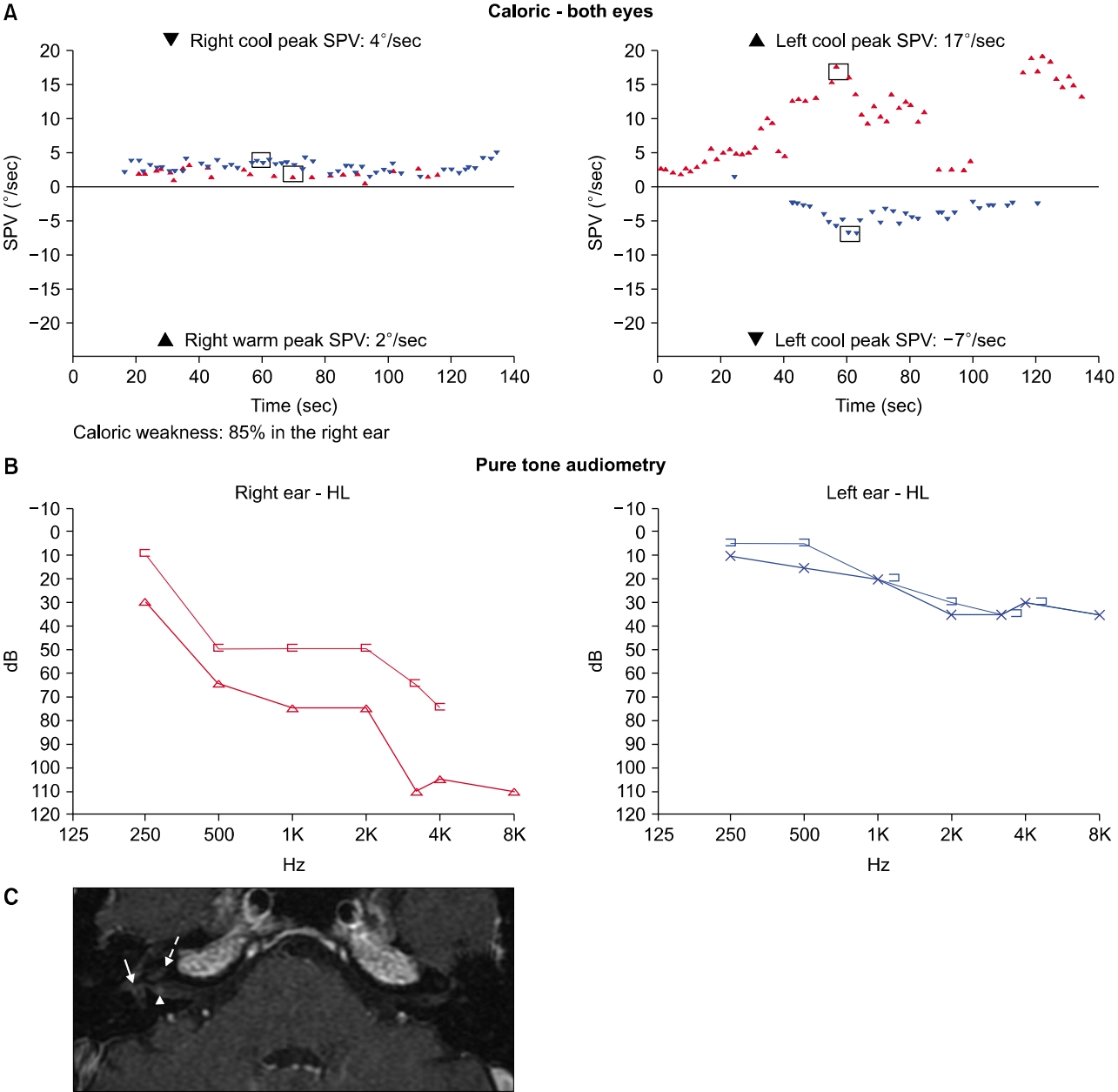

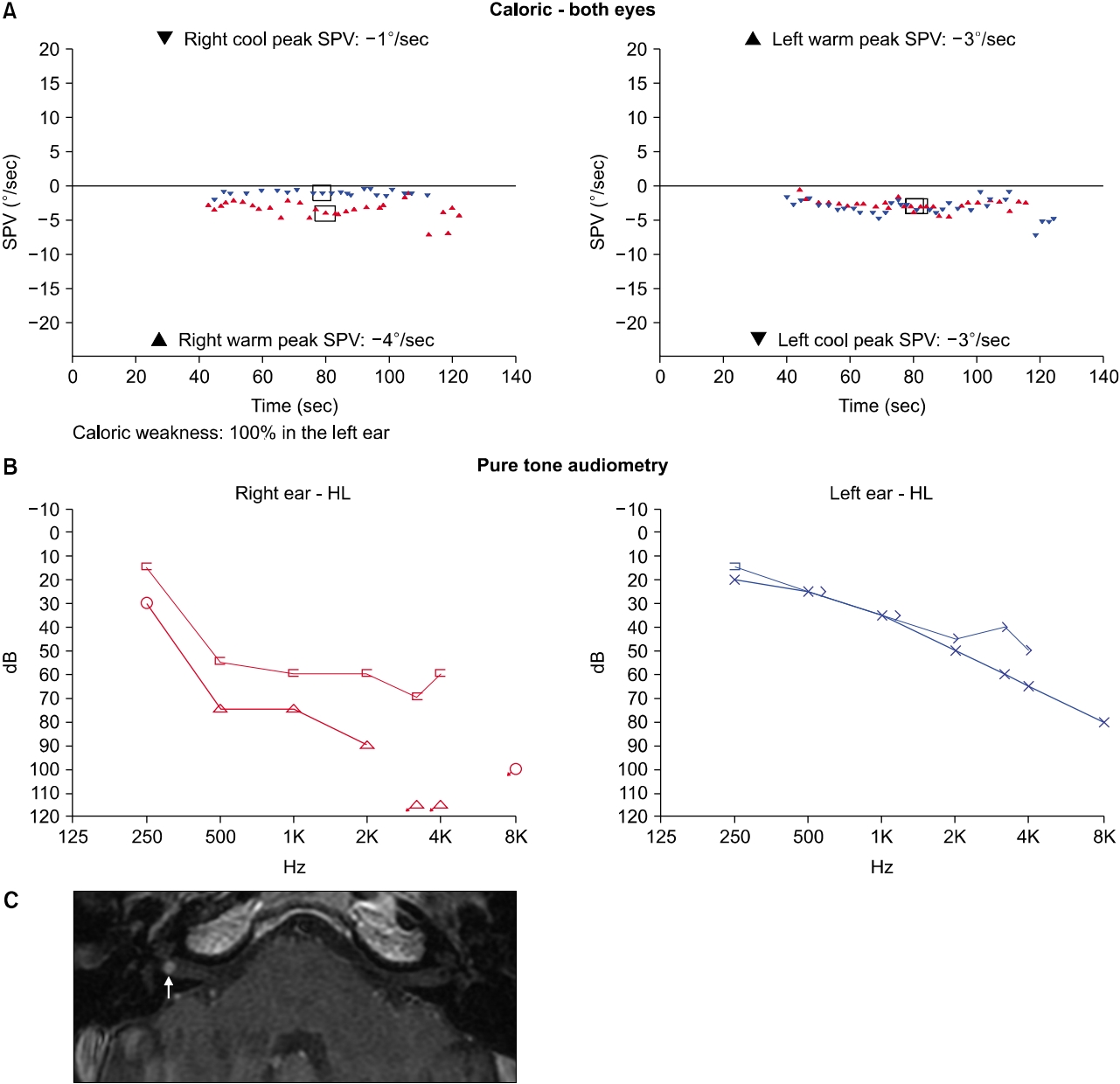

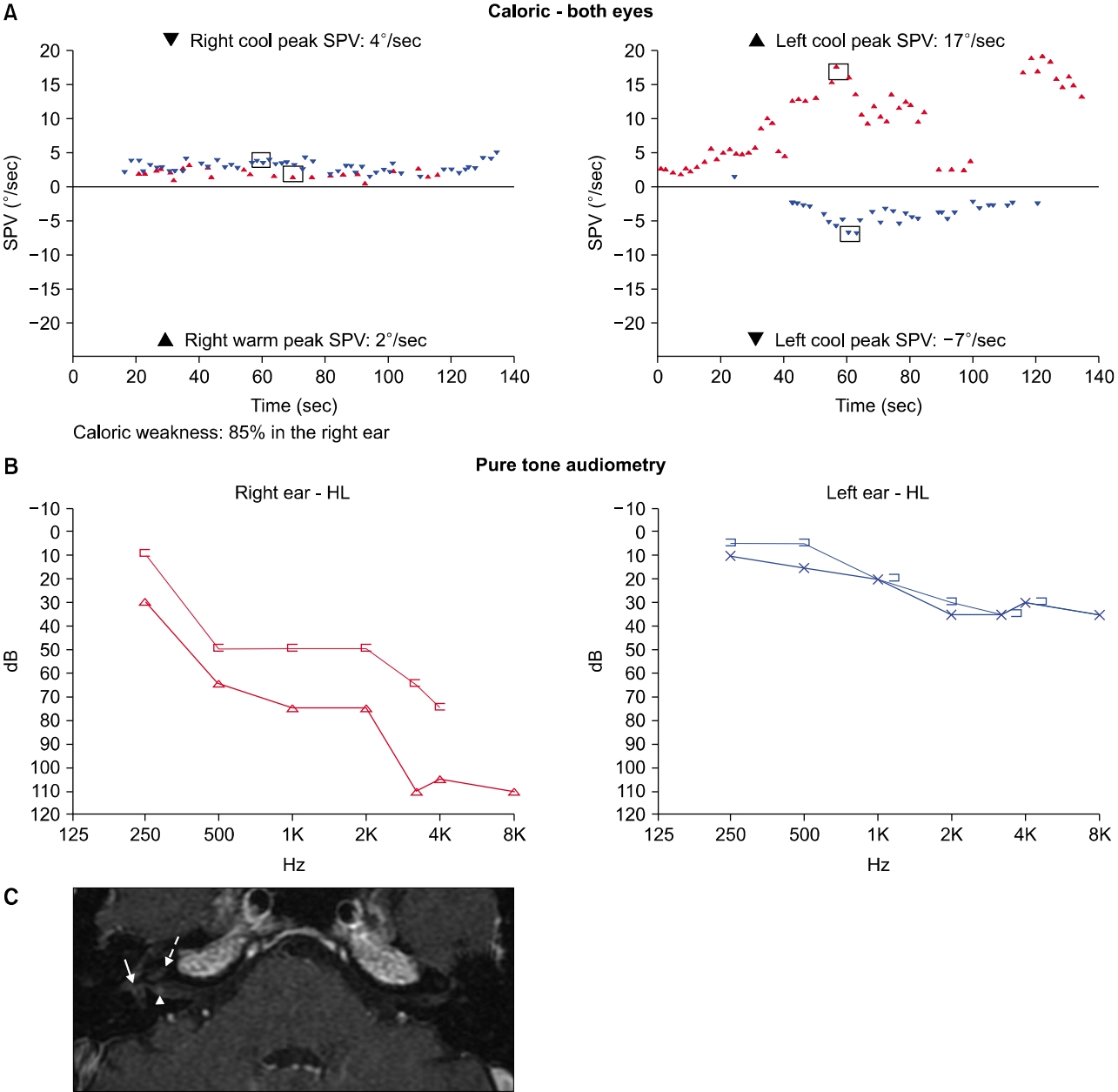

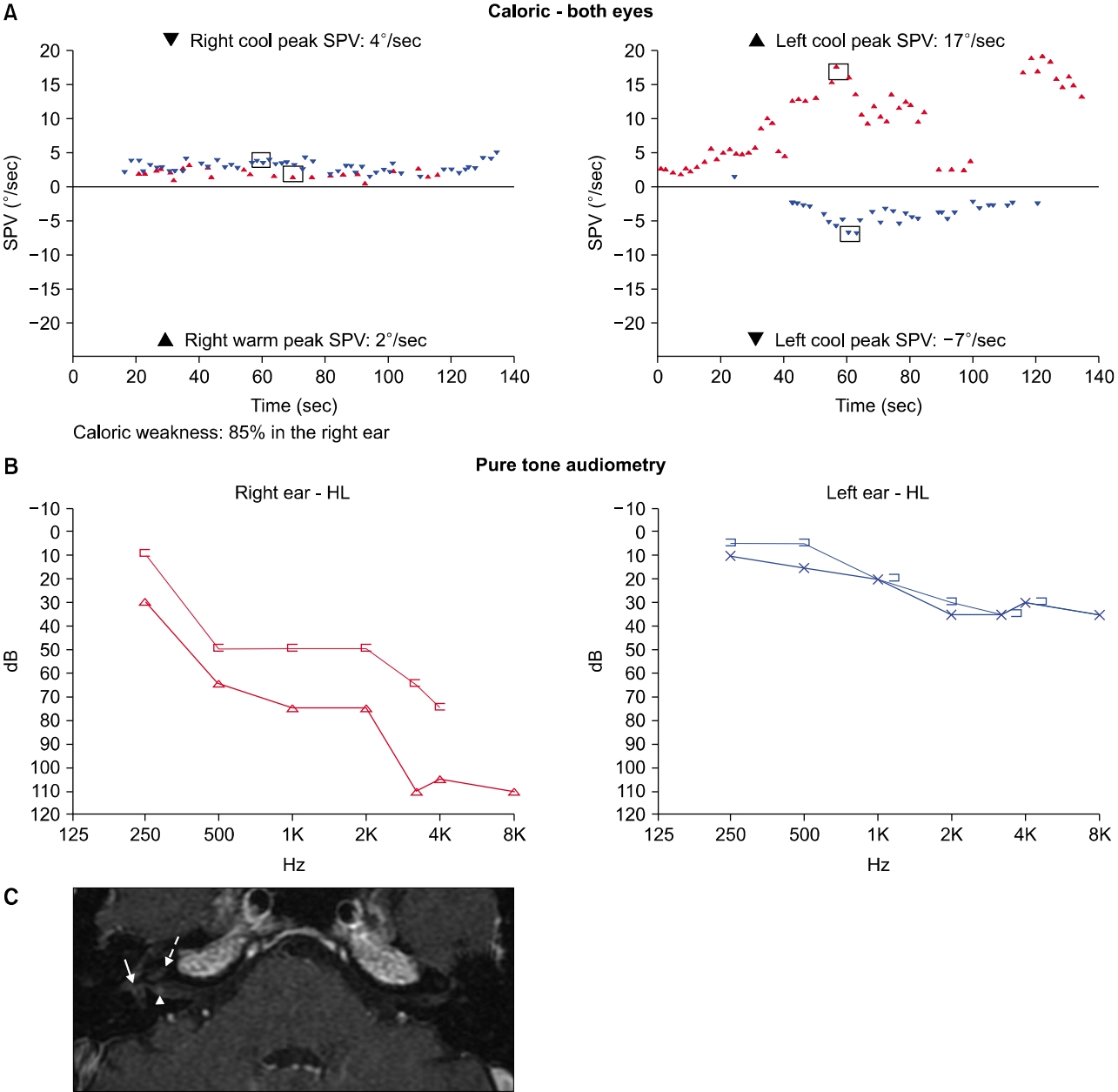

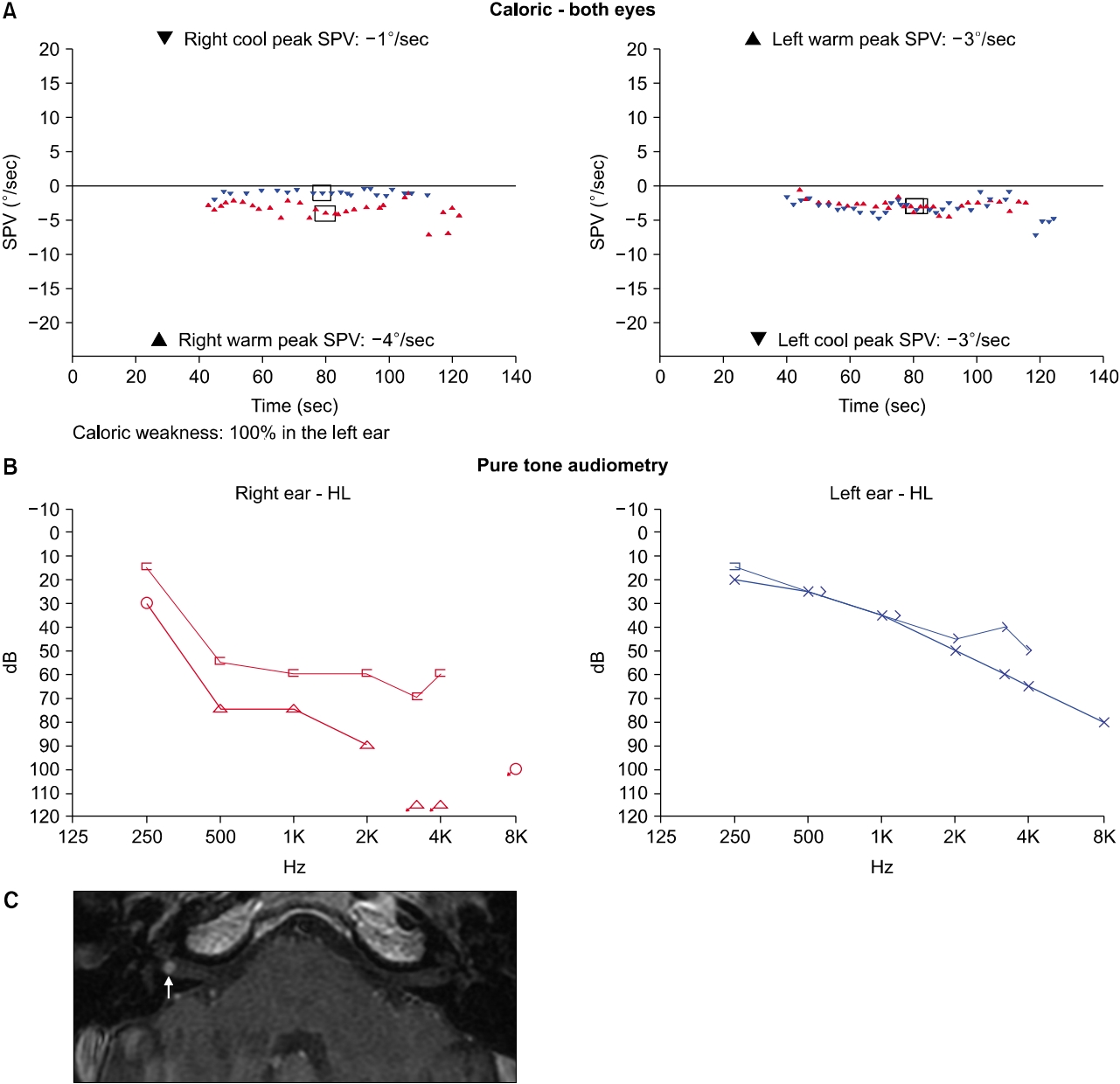

The second vertigo attack occurred 6 years after the first attack. The patient was admitted to our department with acute vestibular syndrome without auditory symptoms. Video nystagmography showed right-beating spontaneous nystagmus (Supplementary Video 2), and bedside head impulse test revealed catch-up saccades on both sides. Neurological examination revealed no other focal neurologic deficit. A bithermal caloric test, compared to that during the first vertigo attack, revealed additional decrease in caloric response on the left side, and the sum of the maximal peak velocities of the slow phase caloric-induced nystagmus for stimulation with warm and cold water on each side was 11°/second (Fig. 3A). PTA, compared to that during the first vertigo attack, showed worsening of hearing threshold on both sides (Fig. 3B), and the patient reported that his hearing had been gradually deteriorating since the first vertigo attack on both sides. IAC MRI revealed a 3 mm-sized intracanalicular mass at the right IAC fundus (Fig. 3C). Rehabilitative treatment through the vestibular rehabilitation therapy was recommended, and the patient did not report any further vertigo attacks, though he experienced mild oscillopsia during gait.

This study was exempted from Institutional Review Board review, and written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

DISCUSSION

RP is a rare, autoimmune disorder which is characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation of multisystemic cartilaginous structures. The etiology of RP is still idiopathic, and an autoimmune response against extracellular cartilage matrix antigen or cartilage immunogenic epitope of chondrocytes have been demonstrated as a possible cause of RP [7]. Otologic manifestation, among which auricular chondritis is the most frequent presenting symptom, in RP is quite common, and evaluation by an otolaryngologist may be required for the proper diagnosis. Inner ear symptoms, such as hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo, may develop in 7% to 42% of RP patients [2-4]. Although inner ear dysfunction in RP is thought to be caused by autoimmune-related inflammation of inner ear structures, other causes including endolymphatic hydrops, destruction of Eustachian tube, and vasculitis in inner ear vessels, have been proposed [8,9]. Hearing loss in RP patients can be found as sudden sensorineural hearing loss, conductive hearing loss, or sensorineural hearing loss type [10-12]. Vestibulocochlear dysfunction may present as bilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss with or without acute spontaneous vertigo [9,12]. Cody and Sones [10] reported that the patients in their study complained of mild dizziness or no dizziness, and acute vestibular syndrome was not reported in any of the patients. Vestibular dysfunction, which is demonstrated by a caloric test, is observed unilaterally or bilaterally in 6% to 13% of RP patients [3,10]. Other studies reported that the feature of vertigo in RP is usually nonpositional with spontaneous nystagmus, and unilateral decrease of caloric response is commonly observed [11,12].

The patient in the present study presented with two episodes of acute spontaneous vertigo at the interval of 6 years. At the first vertigo attack, acute vertigo was accompanied by sudden hearing loss on the right side, and results of vestibular function test suggested acute loss of the right vestibular function. During 6 years between the two episodes of acute spontaneous vertigo, his hearing on both sides was deteriorated gradually, which might have been caused by autoimmune-related inner ear inflammation. At the second vertigo attack, acute vertigo developed without auditory symptoms, and results of vestibular function test suggested acute loss of the left vestibular function. IAC MRI demonstrated mildly enhanced foci in the right vestibule, cochlea, and vestibular nerve, suggesting inflammation in the inner ear structures at the first vertigo attack. At the second vertigo attack, it demonstrated a small enhancing mass in the right IAC fundus, suggesting intracanalicular tumor-like lesion such as vestibular schwannoma or inflammatory nodule. We assume that the size of focal enhancement in the right vestibular nerve at the first attack (arrowhead in Fig. 2C) gradually increased to become a mass-like lesion at the same location (arrow in Fig. 3C). IAC MRI revealed no abnormal findings on the left side either the first or the second vertigo attack.

Kato et al. [13] reported that three-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI, which was taken during the period of acute vertigo in a patient with RP, showed diffuse enhancement throughout the vestibule 4 hours after intravenous gadolinium injection. They concluded that inner ear dysfunction in RP is due to vasculitis, leading to blood-labyrinth barrier breakdown because cartilage is not present in the inner ear [13]. Temporal bone histopathologic study and scanning electron microscopic study demonstrated inner ear findings of endolabyrinthitis such as encapsulated and dislocated tectorial membrane, degeneration of the organ of Corti, but good preservation of the neural elements compared with the marked change in the sensory epithelia [14,15].

In our patient, IAC MRI suggests that the first vertigo attack with sudden hearing loss may be due to neurolabyrinthitis in the right inner ear, but IAC MRI demonstrated no abnormal finding in the left inner ear at the second vertigo attack. This report, to the best of our knowledge, is the first report showing intracanalicular mass in the patient with RP, though the diagnosis of the mass was not pathologically confirmed.

In conclusion, vestibular dysfunction may be presented with separate episodes of acute spontaneous vertigo in RP, and sudden hearing loss may or may not be accompanied by acute vertigo.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

-

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (2019R1H1A1080123).

Supplementary Materials

Fig. 1.(A) The patient’s ear showed pinna deformity with cauliflower appearance. Eye examination revealed episcleritis (B), and saddle nose deformity (arrow) was shown (C). (D) Chest computed tomography demonstrated diffuse thickening of the proximal trachea with calcification (arrow).

Fig. 2.Results of laboratory tests and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during the first vertigo attack. (A) A bithermal caloric test demonstrates canal paresis of 85% in the right side. (B) Average pure tone threshold (0.5 kHz+1 kHz+2 kHz+3 kHz/4) was 81 dB in the right ear and 26 dB in the left ear. (C) Internal auditory canal MRI demonstrates mild focal enhancement in the vestibule (arrow), cochlea (dotted arrow), and vestibular nerve (arrowhead), suggesting combined labyrinthitis and neuritis. SPV, slow-phase velocity; HL, hearing level.

Fig. 3.Results of laboratory tests and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during the second vertigo attack. (A) A bithermal caloric test demonstrates decreased caloric responses in both sides. (B) Average pure tone threshold (0.5 kHz+1 kHz+2 kHz+3 kHz/4) was 90 dB in the right ear and 43 dB in the left ear. (C) Internal auditory canal (IAC) MRI demonstrates a 3 mm-sized small mass in the right IAC fundus (arrow). SPV, slow-phase velocity; HL, hearing level.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jaksch-Warnenhorst R. Polychondropathia. Wien Arch F Inn Med 1923;6:33–100.

- 2. McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:193–215.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Michet CJ Jr, McKenna CH, Luthra HS, O’Fallon WM. Relapsing polychondritis. Survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:74–8.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Zeuner M, Straub RH, Rauh G, Albert ED, Schölmerich J, Lang B. Relapsing polychondritis: clinical and immunogenetic analysis of 62 patients. J Rheumatol 1997;24:96–101.PubMed

- 5. Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis: report of ten cases. Laryngoscope 1979;89(6 Pt 1):929–46.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Takwoingi YM. Relapsing polychondritis associated with bilateral stapes footplate fixation: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2009;3:8496. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, Gorochov G, Amoura Z. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:90–5.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, Foerger F, Knopf A, Heemann U, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:540–6.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Kumakiri K, Sakamoto T, Karahashi T, Mineta H, Takebayashi S. A case of relapsing polychondritis preceded by inner ear involvement. Auris Nasus Larynx 2005;32:71–6.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Cody DT, Sones DA. Relapsing polychondritis: audiovestibular manifestations. Laryngoscope 1971;81:1208–22.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Tsuda T, Nakajima A, Baba S, Tanohara K, Masuda I, Yamada T, et al. A case of relapsing polychondritis with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and perforation of the nasal septum at the onset. Mod Rheumatol 2007;17:148–52.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Issing WJ, Selover D, Schulz P. Anti-labyrinthine antibodies in a patient with relapsing polychondritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1999;256:163–6.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Kato M, Katayama N, Naganawa S, Nakashima T. Three-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging findings in a patient with relapsing polychondritis. J Laryngol Otol 2014;128:192–4.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Hoshino T, Ishii T, Kodama A, Kato I. Temporal bone findings in a case of sudden deafness and relapsing polychondritis. Acta Otolaryngol 1980;90:257–61.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Hoshino T, Kato I, Kodama A, Suzuki H. Sudden deafness in relapsing polychondritis. A scanning electron microscopy study. Acta Otolaryngol 1978;86:418–27.PubMed

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

KBS

KBS

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite