Abstract

- The absence of a temporal bone overlying the superior semicircular canal causes superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD). The vestibular symptom of SSCD syndrome (SCDS) is vertigo and audiologic symptoms include autophony, hyperacusis, and ear fullness. A 52-year-old man presented with left-sided unilateral hearing loss, aural fullness, and recurrent spinning-type vertigo. He had positive Hennebert sign and mixed-type hearing loss, with a prominent low-frequency air-bone gap. These symptoms reminded us of SCDS, and computed tomography (CT) revealed SSCD. However, the patient had not experienced vertigo until 1 week prior to the visit. In addition, the audiogram revealed fluctuation of hearing, which was aggravated when the vestibular symptoms manifested. Vertigo might be due to Menière’s disease rather than SCDS and SSCD was incidentally detected on CT. According to reviews, this is no reported case of SCDS manifested as Menière’s disease, so we report this case with a brief review of the literature.

-

Keywords: Semicircular canal dehiscence; Superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome; Menière’s disease; Hearing fluctuation

-

중심단어: 세반고리관 피열, 상반고리관 피열증후군, 메니에르병, 청력 변동

INTRODUCTION

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD) occurs owing to the absence of a temporal bone overlying the superior semicircular canal [1]. Vestibular symptoms caused by sound and pressure stimuli describe this condition. Patients may experience vertigo and/or oscillopsia induced by loud sounds and pressure changes in the external auditory canal, known as the Tullio phenomenon and Hennebert sign, respectively. The acoustic signs of SSCD include autophony, hyperacusis, and ear fullness. A common audiologic characteristic of SSCD syndrome (SCDS) is conduction hearing loss at low frequency and is specified by a lower bone-conduction sound threshold in audiometry [2].

Although the clinical symptoms of SSCD are well known, vestibular and audiologic symptoms may not always be present simultaneously [3]. Audiologic symptoms may present with or without vestibular symptoms. Furthermore, audiologic symptoms in SSCD can manifest in several ways, such as mixed, conductive, and sensorineural hearing loss, and normal hearing [3,4].

We report the case of a 52-year-old male patient, who presented with unilateral hearing loss, with fluctuation of hearing impairment and repeated spinning-type vertigo. The patient was later diagnosed with SSCD; however, clinical manifestations were consistent with Menière’s disease.

CASE REPORT

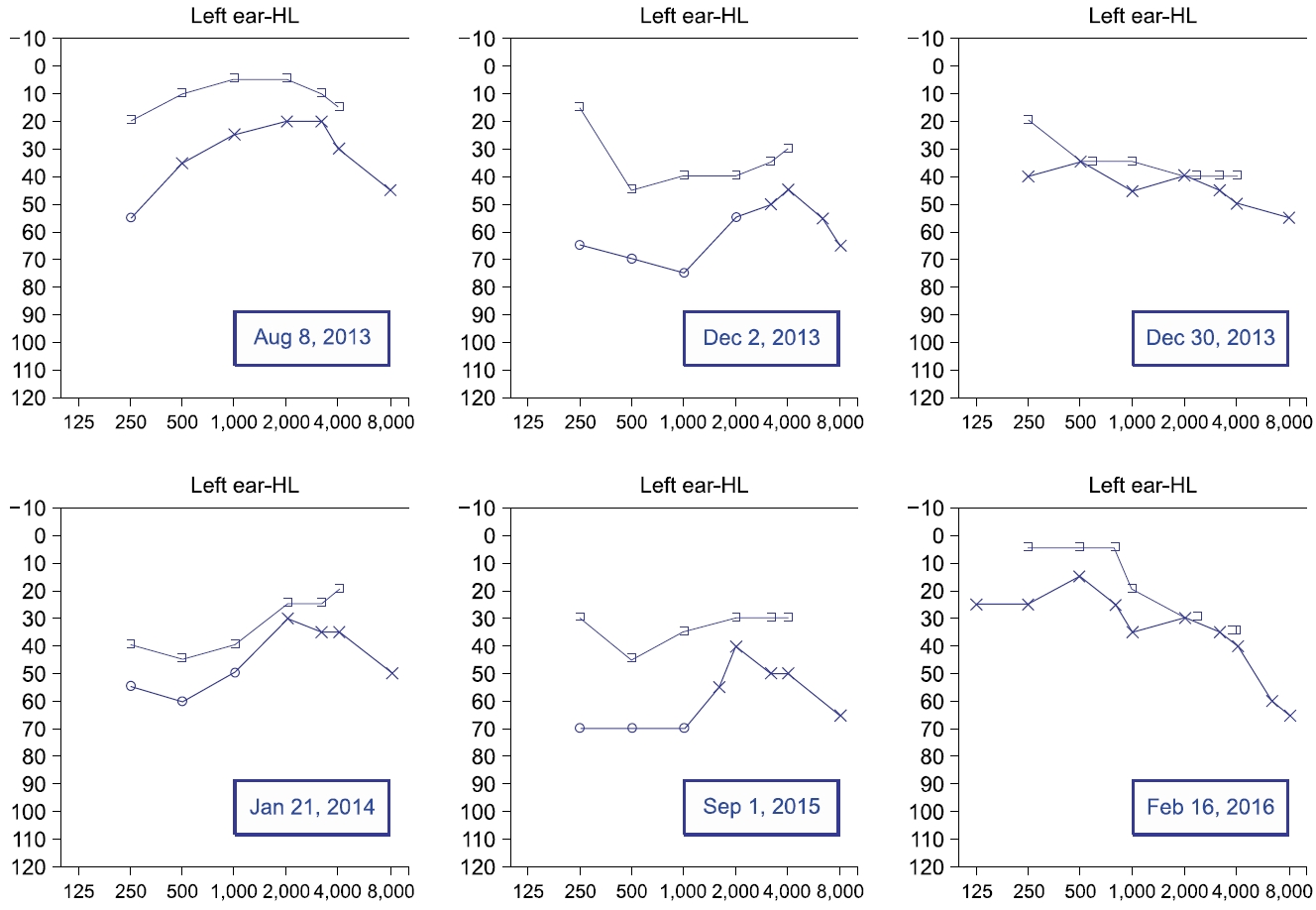

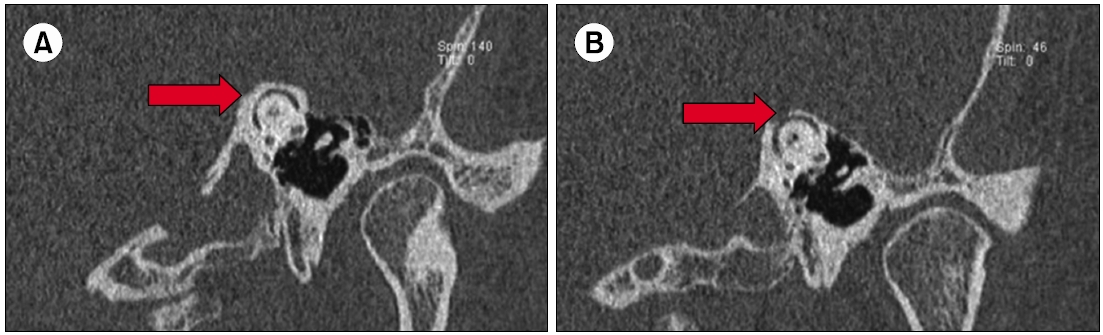

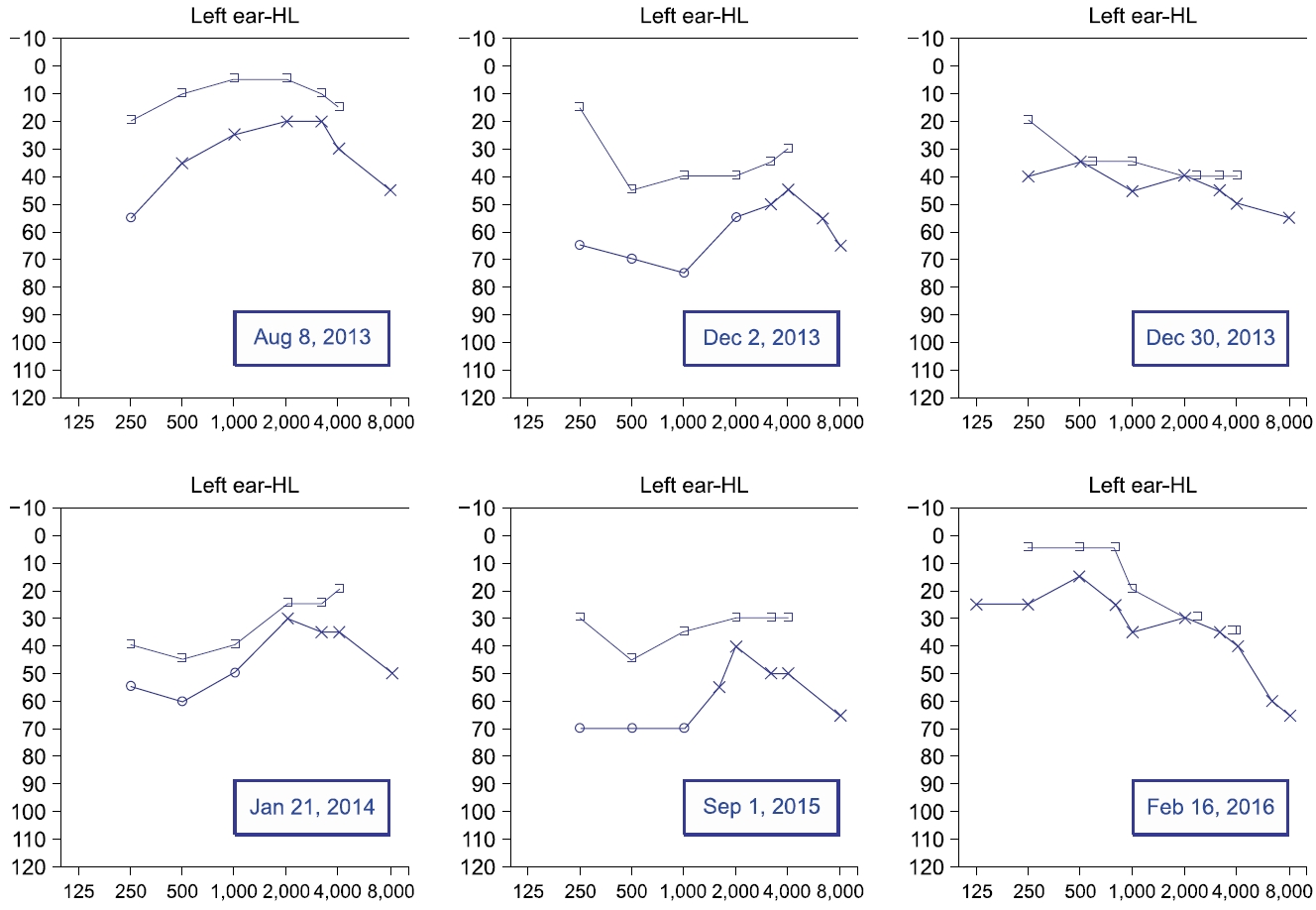

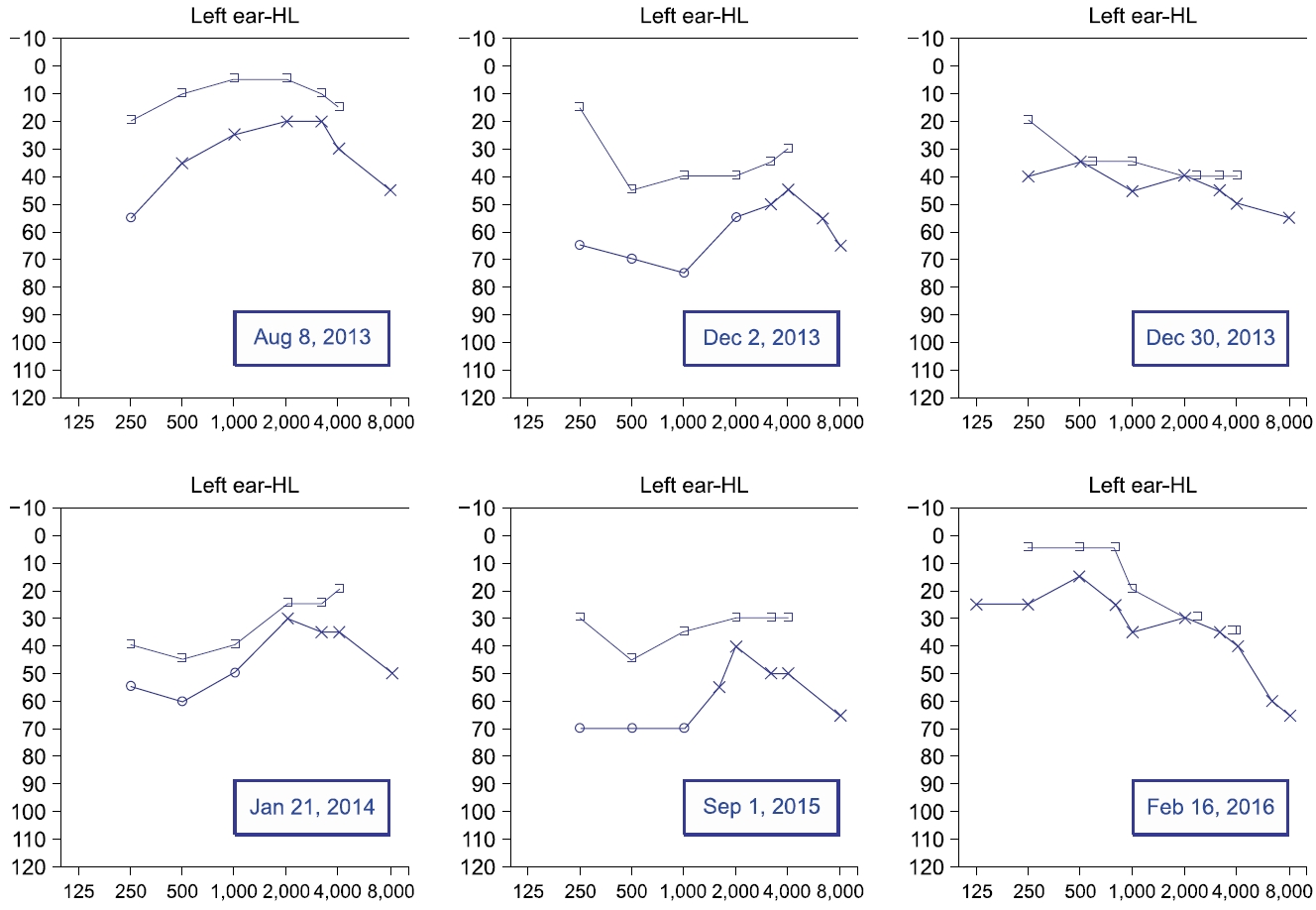

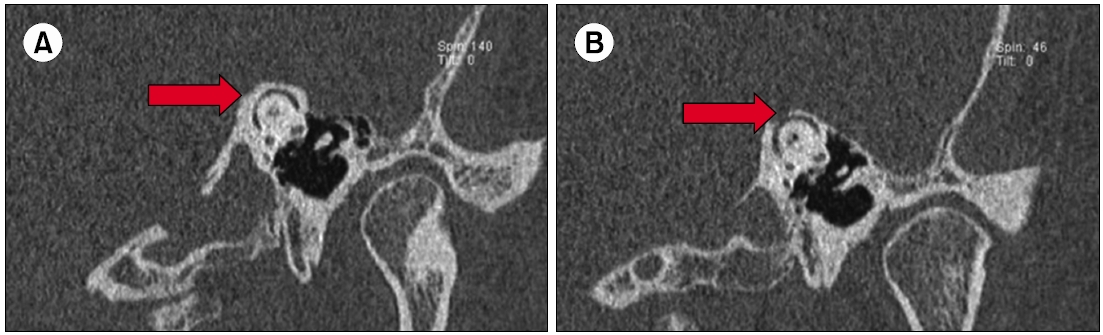

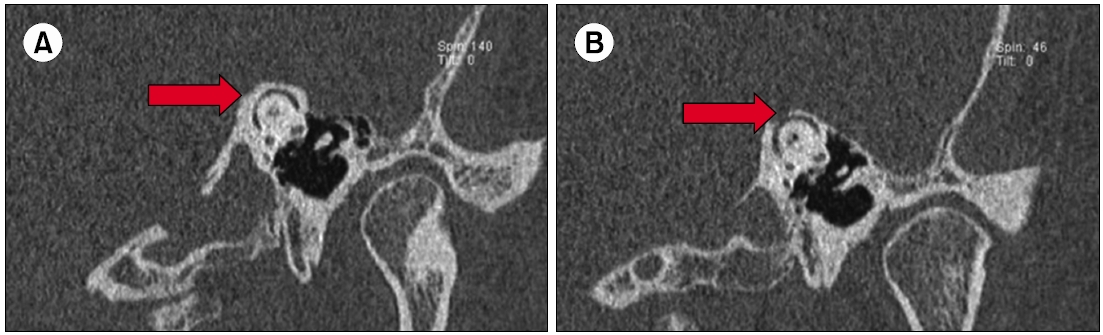

A 52-year-old male patient presented with left-sided unilateral hearing loss, aural fullness, and recurrent spinning-type vertigo. These symptoms had been initiated 1 week before the visit. Vertigo occurred spontaneously, repeated several times, lasted 3 to 4 hours, and was aggravated by loud noises. He had no known history of chronic disease, trauma, or other otologic symptoms, such as otalgia and otorrhea. Otoscopic examination of the eardrums revealed normal results. He had no spontaneous nystagmus and no nystagmus could be observed after head shaking and positional changes. However, the Hennebert sign (eye movements evoked by pressure changes in the external auditory canal by compressing tragus) was positive in the left ear, which induced mild dizziness. In the left ear, positive pressure evoked a conjugate vertical-torsional ocular deviation where the eyes rotated up and away from the left ear. This reversed with negative pressure. No nystagmus could be triggered with pressure changes in the right external auditory canal. The audiologic test showed mixed-type hearing loss in the left ear with an average pure tone of 25 dB and approximately 17 dB air-bone gap (Fig. 1). To evaluate the cause of mixed-type hearing loss, a temporal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which showed 1.8 mm long SSCD on the left side. There was no inflammatory soft tissue in both the middle ear cavity and mastoid, with normal ossicles (Fig. 2).

For initial treatment, oral steroid (methylprednisolone) was prescribed 20 mg per day for 1 week, 12 mg per day for 1 week, and 8 mg per day for 1 week for a total of 3 weeks. After the treatment, the patient’s audiologic and vestibular symptoms improved; however, relapse occurred. This fluctuation in symptoms was repeated over a month. The audiologic test findings also fluctuated (Fig. 1).

As the symptoms did not improve, further evaluations, including brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and vestibular function tests, were performed. MRI revealed no remarkable findings. A bithermal caloric test showed 38% left-sided canal weakness with normal directional preponderance. On cervical vestibular-evoked myogenic potential (cVEMP) there was no response on the left side at 100 dB evoked sound.

The patient was treated for Menière’s syndrome. Isosorbide dinitrate (60 mg/day) and dexamethasone intratympanic injections were administered four times. The vestibular symptoms improved. Moreover, the audiologic symptoms recovered with an average pure tone of 20 dB. The patient showed no Menière attack during follow-up, so he refused any surgical intervention for SSCD.

DISCUSSION

The vestibular symptom of SCDS is vertigo, which is triggered by sound and pressure stimuli. Loud sounds and changes in pressure in the external auditory canal may cause vertigo and/or oscillopsia in patients, known as the Tullio phenomenon and the Hennebert sign, respectively [1]. The mechanism of vertigo in SCDS is due to the effect of dehiscence during pressure transmission into the inner ear. The dehiscence creates a third window in the inner ear, which allows the superior semicircular canal to respond to sound and pressure stimuli. A loud sound pressure, positive pressure in the external auditory canal, or Valsalva maneuver induces ampulofugal flow of the endolymph in the superior semicircular canal. Consequently, after exposure to these stimuli, the patient will have upward and torsional movement of the eye away from the affected ear [2]. In contrast, Müller maneuver (Valsalva against a closed glottis), the negative pressure in the external auditory canal, induces ampulopetal (inhibitory) flow of the endolymph in the superior semicircular canal. Thus, the patient will experience the downward torsional movement of the eye toward the affected ear.

Audiologic symptoms of SSCD include autophony, hyperacusis, and ear fullness. Conduction hearing loss at low frequencies is a common audiologic characteristic of SCDS and is specified by a lower bone-conduction sound threshold in audiometry [2]. Typically, patients with SCD have an air-bone gap of more than 10 dB at low frequencies. This air-bone gap is not caused by a middle ear conductive mechanism. Rather, it is assumed to be caused by the third mobile window effect. The dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal cases the acoustic energy transmitted into the inner ear to dissipate through dehiscence.

Although the vestibular and audiologic symptoms of SCDS are well characterized, the symptoms may not always manifest simultaneously. Patients may experience audiological symptoms with or without vestibular symptoms [3]. Moreover, they may have a variety of audiological manifestations. Chi et al. [4] reported four, three, and two cases of mixed-type, conductive, and sensorineural hearing loss, respectively, and two cases of normal hearing in 11 patients with SCD [4].

Menière’s syndrome causes vertigo, fluctuating low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss, aural fullness, and tinnitus in the inner ear. According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology- Head, and Neck Surgery Foundation guidelines, Menière’s disease is defined as “recurrent, spontaneous episodic vertigo, hearing loss, aural fullness, and tinnitus.” Either tinnitus or aural fullness (or both) must be present on the affected side to make the diagnosis [5]. Sensorineural hearing loss at low frequencies is a common symptom of Menière’s disease. The hearing may fluctuate during the clinical course of the disease. As SCDS may have a variety of audiologic symptoms, those of Menière’s disease is somewhat similar, except for hearing fluctuations.

In our case, the patient had recurrent vertigo, left-sided aural fullness, and hearing loss. He was diagnosed with SCDS after CT scanning of the temporal bone. However, audiologic test data showed fluctuations in hearing in the left ear, which is a characteristic symptom of Menière’s disease. The exact cause of the symptoms of Menière’s disease is unknown. Endolymphatic hydrops is regarded as the basic pathophysiology of Menière’s disease [6].

According to Schuknecht’s postulation [7], the potassiumrich endolymph leaks into the perilymph through the membranous labyrinth ruptures, soaking the vestibulocochlear nerve and hair cells. Elevation of extracellular potassium concentrations depolarize the nerve cells, resulting in their deactivation. This causes a reduction in auditory and vestibular neuronal output, which causes hearing loss and acute vestibular symptoms, as observed in a classic Menière attack [7].

In our case, the patient had repeated whirling vertigo, positive Hennebert sign, and mixed-type hearing loss, with a prominent low-frequency air-bone gap. These symptoms reminded us of SCDS, and a later CT scan revealed SSCD. However, the patient had not experienced vertigo until 1 week prior to the visit. In addition, the audiogram revealed fluctuation of hearing, which was aggravated when the vestibular symptoms manifested. Therefore, the patient might have vertigo due to Menière’s syndrome rather than SCD and was incidentally detected as SCDS using CT. This supports the idea of SCDS being commonly acquired [8]. SCDS is incidentally detected in many cases without symptoms.

Vestibular-evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) is a useful tool for the diagnosis of SCD. Generally, the threshold of the VEMP response is lowered in SCDS [9]. This is related to the lowered impedance for the transmission of sound stimuli due to the third mobile window effect. Consequently, the VEMP stimulus results in a larger activation of the saccule in an ear with SCD than that without SCD.

Although VEMP response in Menière’s disease would present variously in the process of disease, cVEMP results in the definite Menière’s disease were mainly hyporesponse [10]. This is owing to either the distention or rupture of saccular hydrops. Moreover, when the saccular hydrops is not ruptured, the VEMP response returns to normal after the Menière attack [11]. Our patient had no response on the left side at 100 dB evoked sound, indicating vertigo due to a Menière attack. This absence of VEMP response supports the idea that the patient’s vertigo and hearing impairment is caused by Menière attack rather than SCDS. Considering the patient’s vertigo history, fluctuation of hearing, vertigo attack, and absence of VEMP response, we report a case of SCDS manifesting as Menière’s disease.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

-

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Fig. 1.Average pure-tone audiometry of the left ear. Note the fluctuation in hearing in the left ear. HL, hearing level.

Fig. 2.A coronal oblique reformats image of temporal bone computed tomography scan showing superior semicircular canal. (A) Relatively thick bone overlying superior semicircular canal (arrow) is observed on the right side compared to the left. (B) Note the bony dehiscence overlying the left superior semicircular canal (arrow).

REFERENCES

- 1. Minor LB, Solomon D, Zinreich JS, Zee DS. Sound- and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:249–58.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Minor LB. Clinical manifestations of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Laryngoscope 2005;115:1717–27.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Mikulec AA, McKenna MJ, Ramsey MJ, Rosowski JJ, Herrmann BS, Rauch SD, et al. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence presenting as conductive hearing loss without vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2004;25:121–9.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Chi FL, Ren DD, Dai CF. Variety of audiologic manifestations in patients with superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Otol Neurotol 2010;31:2–10.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Basura GJ, Adams ME, Monfared A, Schwartz SR, Antonelli PJ, Burkard R, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Ménière's disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;162(2 Suppl):S1–55.Article

- 6. Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB Jr. Pathophysiology of Meniere’s syndrome: are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otol Neurotol 2005;26:74–81.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Schuknecht HF. The pathophysiology of Meniere’s disease. Am J Otol 1984;5:526–7.PubMed

- 8. Nadgir RN, Ozonoff A, Devaiah AK, Halderman AA, Sakai O. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence: congenital or acquired condition? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:947–9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Streubel SO, Cremer PD, Carey JP, Weg N, Minor LB. Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials in the diagnosis of superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2001;545:41–9.PubMed

- 10. Yoon S, Kim MJ, Kim M. Hyper-response of cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential in patients with Meniere disease: a preliminary study. Res Vestib Sci 2018;17:44–8.Article

- 11. Kuo SW, Yang TH, Young YH. Changes in vestibular evoked myogenic potentials after Meniere attacks. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005;114:717–21.ArticlePubMed

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

KBS

KBS

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite